By Brinda Kashyap, Mrinal Saikia, & Hashinur Rahman Pavel

Rivers do not stop at political borders—but governance often does. As climate change intensifies floods, droughts, and development pressures, cooperation over shared waters is no longer optional. It is essential. Yet translating cooperation from principle into practice remains one of the region’s most persistent challenges.

From 8–11 December 2025, we—youth participants of the Youth for Meghna (Y4M), a basin-based network working across India and Bangladesh under the Barak–Meghna Water Feature Programme (MWFP) of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)—participated in the Pan-Asia Training on International Water Law (IWL) at the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) in Bangkok, Thailand. The training was jointly facilitated by UNECE, IUCN, and partners. Our participation was supported by IUCN through the BRIDGE/TROSA Programme.

Over four intensive days, the training brought together more than 100 participants from across Asia, including practitioners, policymakers, academics, and youth, to explore how international water law can support cooperation, climate-resilient investment, and inclusive governance across Asia’s shared river basins.

When Law Meets Reality

At the heart of the training were the UN Water Convention (1992) and the UN Watercourses Convention (1997)—often cited in policy discussions, but rarely unpacked in terms of how they operate on the ground. Through expert sessions and facilitated group work, we examined core principles such as equitable and reasonable utilisation, the obligation to prevent significant harm, and procedural duties around notification, consultation, and data sharing.

What made these discussions particularly engaging was the emphasis on practice. Simulated negotiations around a hypothetical transboundary basin revealed a familiar pattern across Asia: while cooperation is widely endorsed in theory, operational arrangements—joint monitoring, data exchange, basin institutions—frequently lag due to lack of robust procedural guidance and understanding of international water law principles. The exercises highlighted how gaps in information, unclear procedures, and power asymmetries can quickly undermine trust between riparian states.

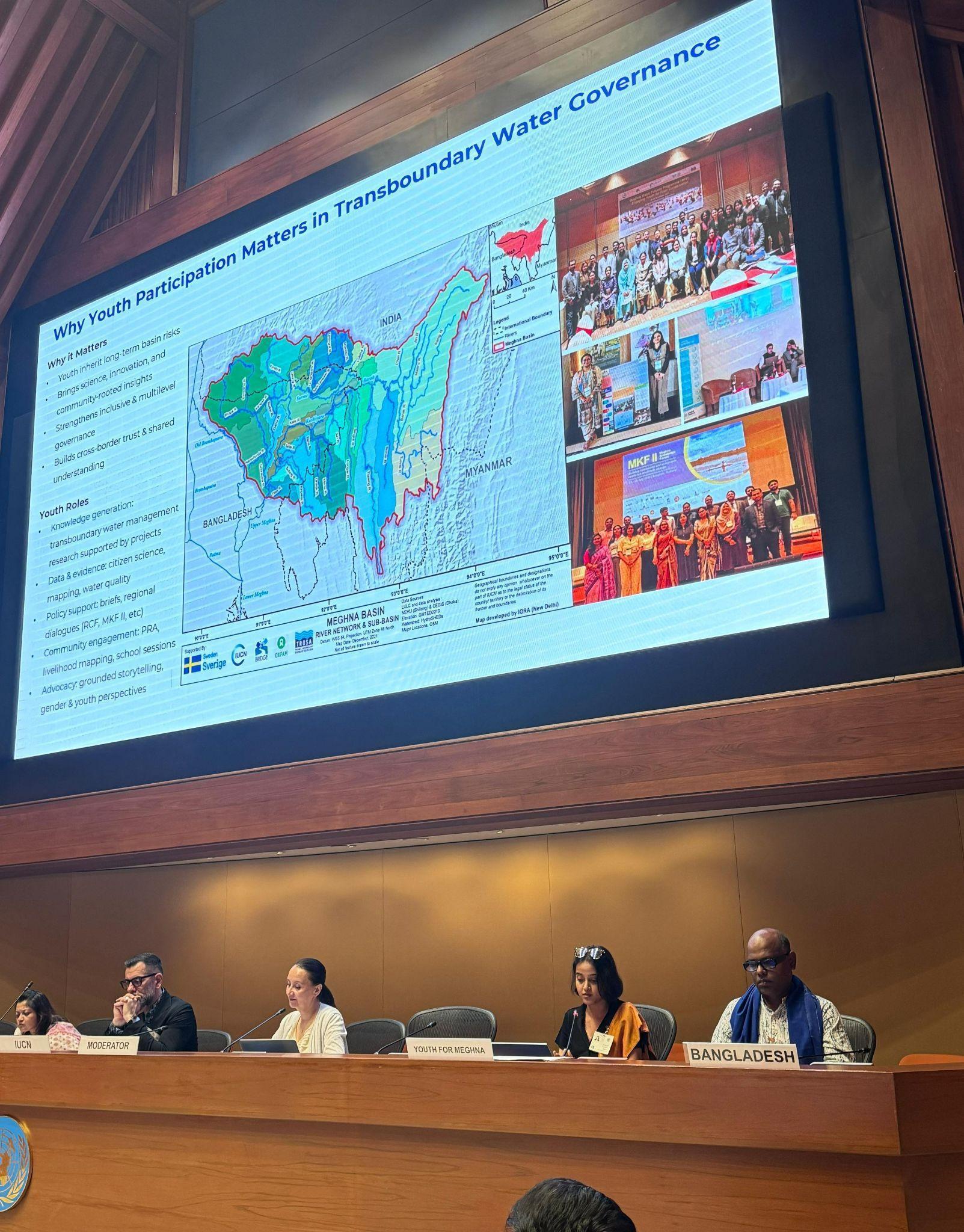

Brinda Kashyap (Y4M member), Presenting during the Gender, Public Participation, Youth, and Information Dissemination in IWL (December 2025)

Dr. Mrinal Saikia (Y4M member) during an interaction session (December 2025)

Why Youth Perspectives Matter

As members of Youth for Meghna (Y4M), we had several opportunities to participate in technical water and NbS dialogues and field missions. This shaped how we approached the simulated negotiations, grounding our reflections in basin-level realities rather than purely abstract legal frameworks. From a youth perspective, the UN Water Convention and the UN Watercourses Convention are not only about treaties and institutions; they are about how governance choices translate into tangible impacts on communities, ecosystems, and livelihoods downstream.

In the Barak–Meghna Basin, shared by Bangladesh and India, this perspective is informed by engagement at the intersection of science, governance, and community practice. Through geospatial analysis, Nature-based Solutions (NbS) assessments, participatory research, and youth storytelling, locally grounded evidence has proven critical in informing basin-wide dialogue. These experiences resonated strongly during the training, illustrating how youth networks can help bridge persistent gaps—between data and decision-making, and between formal legal commitments and lived realities.

Connecting Law, Data, and Ecosystems

Across the training sessions, data and joint assessment emerged less as technical tools and more as the connective tissue of transboundary cooperation. Case studies repeatedly demonstrated that while legal frameworks establish obligations, it is shared monitoring systems, comparable datasets, and agreed assessment processes that determine whether those obligations can be operationalised in practice.

Ecosystem-focused sessions further reinforced this point. Discussions on wetlands, aquifers, sediment dynamics, mining and pollution, and basin-scale Nature-based Solutions showed how ecological processes often cut across administrative and political boundaries, exposing both the strengths and fragilities of existing governance arrangements. In this sense, ecosystems functioned as real-world tests of cooperation—revealing where institutional coordination, information exchange, and joint decision-making were sufficient, and where they remain fragmented.

From left to right, Vishwa Ranjan Sinha (Senior Programme Officer, IUCN) with Mrinal, Brinda, and Pavel, training participants from Youth4Meghna at the United Nations Conference Centre (UNESCAP). Bangkok, December 2025

Looking Forward

For many across Asia, global water conventions are sometimes perceived as distant or abstract. This training reinforced that their real strength lies in the procedural norms they promote—transparency, consultation, cooperation, and accountability. These norms are increasingly vital as climate uncertainty reshapes water risks and shared river basins face growing pressure.

What stayed with us most was seeing how cooperation succeeds—or falters—in practice. Climate adaptation discussions often overlook transboundary realities; legal tools can remain academic without clear pathways to implementation; and data, monitoring, and joint assessments are unevenly applied across basins. Observing these contrasts—between contexts with established systems and those still translating commitments into action—sharpened our understanding of where evidence-based approaches can most effectively support decision-making.

The experience also highlighted the value of creating greater space for exchange and learning, particularly for young professionals seeking clearer entry points into transboundary water governance. As pressures on Asia’s shared rivers continue to grow, the future of cooperation will depend not only on laws and institutions, but on the ability to integrate science, ecosystems, and inclusive participation.

From riverbanks to rulebooks, youth have a role to play—and a responsibility to engage.